An International Traveling Exhibition

by Calley O'Neill and the Rama Team, Featuring Rama, the Artist Elephant

A JOURNEY OF ART AND SOUL FOR THE EARTH

RAMA: AMBASSADOR FOR THE ENDANGERED ONES

Speaking Passionately on Behalf of Those who Cannot Speak

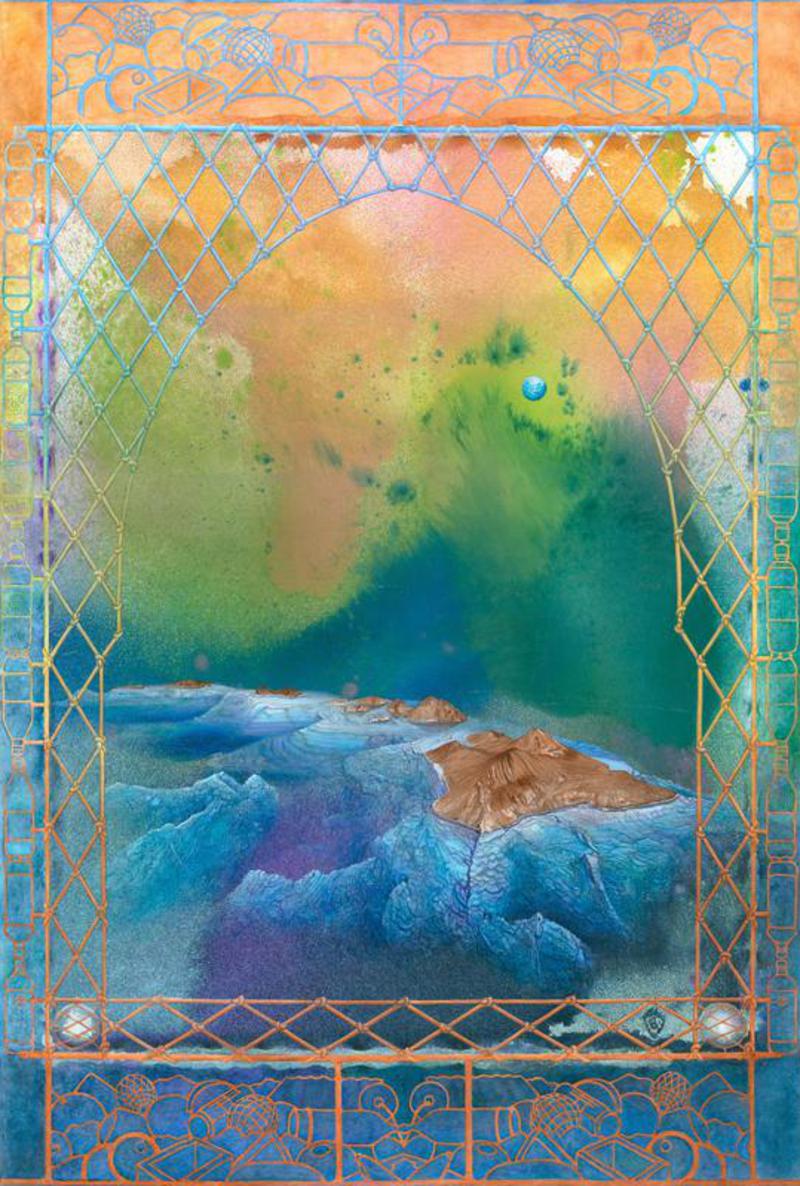

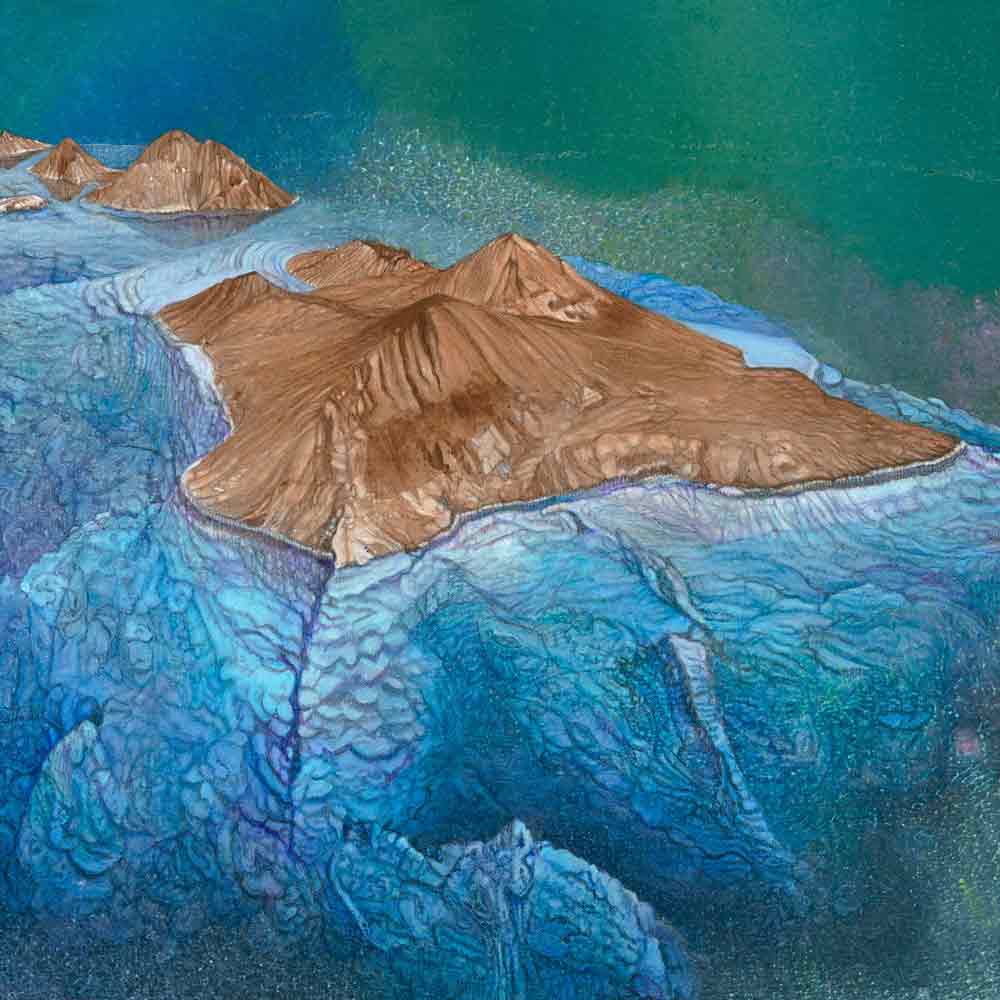

OCEAN GYRES: SWIRLING IN A SEA OF PLASTIC

by Calley O’Neill and Rama the Elephant with Jeb Barsh

Already deep into this painting, I kept wondering. What is the theme? What is this painting about? What does this painting need and want to say? It’s an invitation, to what awareness? To take what action? Everyday I would question this. For months on end, nothing came, until I saw this movie. With a disturbing, sinking feeling walking back from the movie, I realized the painting was about plastic pollution. I came to grips with the fact that every bit of plastic ever created still exists in the biosphere, as plastic. Every bit. All the billions and billions of bottles, bags, brushes, balls and barrels. All of it.

| ||||

Hearing about it more and more often, I had a lot of questions about The Great Pacific Garbage Patch, and wondered what it is, how big it really is, how many ocean gyres there are, what was really going on, and what could be done to clean it up. What is the vortex of plastic soup in the middle of the sea known as The Great Pacific Garbage Patch, one of five ocean gyres, where the ocean swirls and gathers plastics. So did surfer/filmmaker Angela Sun. Her film, PLASTIC PARADISE: THE GREAT PACIFIC GARBAGE PATCH, takes one on a compelling journey to find out the truth about plastic pollution, the ocean's health and how plastic pollution is affecting ocean wildlife, and potentially, our life.

Here's an excellent summation from Wikipedia:

The Great Pacific garbage patch has one of the highest levels known of plastic particulate suspended in the upper water column. As a result, it is one of several oceanic regions where researchers have studied the effects and impact of plastic photodegradation in the neustonic layer of water.[25] Unlike organic debris, which biodegrades, the photodegraded plastic disintegrates into ever-smaller pieces while remaining a polymer. This process continues down to the molecular level.[26] As the plastic flotsam photodegrades into smaller and smaller pieces, it concentrates in the upper water column. As it disintegrates, the plastic ultimately becomes small enough to be ingested by aquatic organisms that reside near the ocean's surface. In this way, plastic may become concentrated in neuston, thereby entering the food chain.

Some plastics decompose within a year of entering the water, leaching potentially toxic chemicals such as bisphenol A, PCBs, and derivatives of polystyrene.[27]

There is riveting footage of Sun’s visit to tiny Midway Atoll, half way between the west coast of the US and Asia at the northwestern tip of the Hawaiian Archipelago in the Papahanaumokuakea Marine National Monument. Witnessing thousands of native sea birds, particularly Laysan Albatross, nesting around millions of plastic nets, computer bits, toys, toothbrushes, and bottles is disturbing and motivating.

We can choose every day to make a difference with each product we buy, or in this case, don’t buy. This we know.

One-use plastics? There are better solutions and they have started. Note Seventh Generations well designed new molded cardboard laundry detergent bottle, with just a thin lining of plastic. We put a man on the moon. We photographed Mars. We are creating solar wing jets. Your computer fits in the palm of your hand. Biodegradable containers can be manufactured. It’s all about demand and the will to change.

Let’s work together to drive demand for the return of enterprises like main street soda fountains, local soda production (Hawaii apparently had many local soda companies); local dairies that make yogurt and kefir in returnable jars, that otherwise always come in one-use plastics. It’s part of the work toward a wonderful, healthy sustainable future.

As we create and hold fast to our dreams of a good future, “The Great Work” will accelerate.

While one day I trust some organism or mushroom or biological process will work to dissolve the plastic ocean soup, for the present, plastic doesn’t go away, and in any case, there is no 'away'. We created plastic. It is a 'perfect' persistent pervasive material that degrades into ever smaller and smaller bits and particles, but doesn’t go away. It’s the most ingenious material we manufacture, and one of the most polluting. It’s meant to last a lifetime and we manufacture into products that we use for a drink or to carry food for a few minutes.

Then we are stuck with the residue. And the bad news is that the small insidious particles are tremendously difficult (currently impossible) to remove from the sea and do more damage to ocean life than the big flotsam and jetsam. Nets are another story altogether. They are much bigger, stronger and longer than I realized and made of tough nylon; they persist and roll like giant tumbleweeds in the ocean, breaking off living corals and killing literally millions of animals as they drift.

The main culprit is one-use plastics, primarily plastic food and water containers and bags. Many say this problem needs to be solved at the consumer level. If we don’t buy them, they won’t make them, yet, the truth is, to be practical, this problem needs to be solved at the front end with a swift transition on both sides of the coin. We no longer buy the plastics. Glass and metal can be recycled. Plastic can only be downcycled to a less valuable pellet form, with more limited usage.

The process of disintegration means that the plastic particulate in much of the affected region is too small to be seen. In a 2001 study, researchers (including Charles Moore) found concentrations of plastic particles at 334,721 pieces per km2 with a mean mass of 5,114 grams (11.27 lbs) per km2, in the neuston. Assuming each particle of plastic averaged 5 mm × 5 mm × 1 mm, this would amount to only 8 m2 per km2 due to small particulates. Nonetheless, this represents a very high amount with respect to the overall ecology of the neuston. In many of the sampled areas, the overall concentration of plastics was seven times greater than the concentration of zooplankton. Samples collected at deeper points in the water column found much lower concentrations of plastic particles (primarily monofilament fishing line pieces).[9] Nevertheless, according to the mentioned estimates, only a very small part of the plastic would be near the surface.

Water and air, the two essential fluids on which all life depends, have become global garbage cans.”

― Jacques-Yves Cousteau